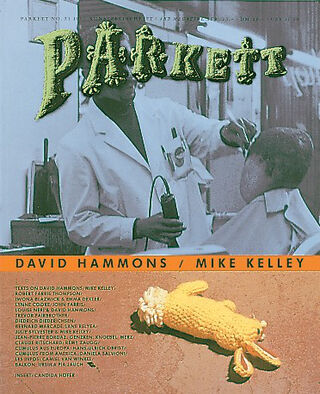

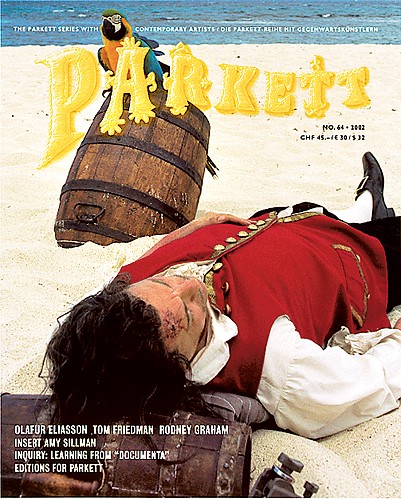

Soft Cover, German, Thread Stitching, 288 Pages, 2002

Parkett No. 64 / 2002

availability unknown, if interested please write an email

On immersing oneself in the working practice of the collaboration artists in this issue, one soon surrenders to the feeling of observing strange, eccentric scientists.

Olafur Eliasson creates sophisticated but elemental models to examine the conditioning of perception, above all the act of seeing itself; Rodney Graham devotes himself “body and soul” to states of consciousness, altering them artificially if need be; and Tom Friedman is as meticulous as a watchmaker in his concentration on the non-technical, non-mechanical and daily reality of the “blind spot.”

Rodney Graham works both with 35-mm film format and LSD. Tom Friedman uses chewing gum, spider legs, Styrofoam cups or single hairs, and Olafur Eliasson, water (in all aggregate states from ice to drizzling rain to fog), mirrors, light, and an endless array of equipment or constructions. Simultaneous immersion and detachment seem to have motivated the process of production, engendering astonishment at the miraculous results. We are presented with possibilities of cheerfully escaping the confinement of familiar, routine patterns, and once again confronted with the fact that reality is a construct and the idea of nature influenced by civilization.The metaphor of the laboratory has repeatedly served the purposes of art and also the venues of its mediation. It is said that in museums all things experimental fall by the wayside in the act of canonizing art or in the growing populist demands that are being made on institutions. And yet professionals closely associated with contemporary art (for example, Alexander Dorner at the Landesmuseum in Hannover in the 1920s, or the pioneers of “documenta”) are the ones who postulated experimental research in the museum. In view of “documenta 11,” we initiated a large-scale inquiry in which personal statements by professionals and practitioners, museum people versed in contemporary art and former directors of the “documenta” provide wideranging insight into current problems, wishes, certainties, and objections as well as possible approaches to overcoming the ruts of time. Its title: Learning from “documenta.”The allusion to the oft-quoted publication of 1972, Learning from Las Vegas, by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, could be read as an indication that, in contrast to their argument at the time, as far as art is concerned, “discovering” and defending the taste of the masses is no longer of relevance. If such a venerable institution as the Guggenheim can make an incursion into the world city of gambling entertainment, then where are the ideals and the potential of culture tucked away: where are they to be (re)discovered? Language: English/German